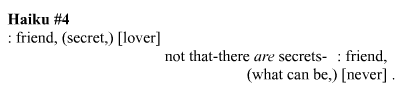

So, yesterday Renarrate asked me what I meant by saying punctuation can be powerful, so we’re going to look at one of my old Haiku poems. I was ridiculously infatuated with E. E. Cummings at the time (still am to a degree), and was absolutely blown over with my own cleverness. I’ve since realized that it’s probably a little too esoteric for the average reader to enjoy, which would be why I haven’t shared it on this blog before. This is it in it’s original formatting with all the punctuation:

Stripped of everything but basic Haiku form, that reads:

friend secret lover

not that there are secrets friend

what can be never

So, here’s the deal with punctuation. Technically, any non-phonetic symbol on the page is considered punctuation. This means your quotation marks (“”), your brackets ([]), your apostrophes (‘), your parentheses (), as well as your periods (.), exclamation marks (!), question marks (?), commas (,), and everything in between (~,@,#,$,%,^,&,*,*,<,>,{},|,`,,/). Before you get on me about the inaccuracy of calling some of those symbols punctuation, remember we’re working from an artistic (poetic) definition of punctuation, and that is slightly different than the grammar definition.

The poetic definition includes every symbol you can think of because every time you reach one of those symbols, as a reader, you have to slightly shift the way you’re thinking and introduce a non-phonetic translation into your thought process. Or to put it another way, every time you see something that isn’t a word, your brain suddenly has to figure out what the fuck to do with those non-word symbols.

This is why punctuation is important to a poet.

We tend to take it for granted because the normal punctuation marks, your periods, exclamation points, question marks, commas, and old-timey line ending semi-colons have their meanings practically hardwired into us the same way words are. To our brain, they are simply a different sort of word, but the far zanier symbols on a keyboard take a little more context to pull any meaning from.

This means that as a poet you can use the symbols in creative ways. One of the simpler things is using parentheses or brackets to group words or phrases together. As demonstrated in the example haiku, there are two such pairings, “secret,” – “what can be,”, and “lover” – “never”. This technique is useful if you want to create what I’ve taken to calling a “layered” poem, or a poem that changes based upon the method of reading, having several possible intended routes through. The more creative of these poems can have stanzas or lines read in any conceivable order, and still carry the intended meaning.

You don’t have to write like that, but it can be a wonderful thought exercise.

Another important use of punctuation is to play with the connotations of certain symbols. For example, everyone has seen a colon used to indicate that the following is an example or explanation of the previous statement, but what happens when you remove the previous statement, or leave it unsaid. Suddenly, the reader either discards the symbol entirely (which can be useful, if that’s what you intend), or they take a few moments at least wondering to themselves why the hell you put that there at all. I do this with “: friend” at the beginning of the haiku, making the word a definition, but not indicating what it defines until the second line when it’s paired with the idea “not that-there are secrets- : friend,”. You’ll also note that in most cases the colon is pressed up against a word: like that, but I chose to leave a space (plus an extra space to ensure it was noticeable) in the hopes that the reader might pick up on the fact that those two aren’t a perfect pairing.

The dashes are another example of this. I use dashes a lot to indicate word groups (“dime-dream-dead”, “hip-sway-swagger”), but that only works for “that-there”, the dash at the end of “secrets” just kind of hangs there, in my mind linking back to the first dash creating a contradictory idea “there are secrets” within “not that there are secrets”.

Then there’s the period all alone out there, nothing anywhere near it, despite its normal desire to hug right up against a word. I call this a hanging period, and to me, it has more finality than a normal period. It’s less of an ending of a sentence, and more of an end of itself. Complete, and total.

All of this is experimentation, and you don’t have to take it to this extreme of thought.

In free verse poetry, line lengths are roughly equal to intended breath lengths, and each line should ideally (with some exceptions) be read in a single breath, with breaths between lines. This is important, but in order to exert more control over the way a poem is read, you use punctuation like commas or periods to control non-breath pauses in the poem. These are by nature shorter pauses, but if you’ve ever learned to read music, you understand that a half-beat rest is as important to the melody as a half-measure rest. The silent moments are the frame around your poem, large and small, and the frame can be carefully and meticulously crafted with intricate detail, or it can be rough-cut.

What I’m saying is that you gauge the complexity of the piece, the ideas being interwoven, a more complex piece usually has more punctuation to help indicate there is more going on than a first glance will show, but simpler pieces are usually better without, to show the earnestness and simplicity.

And with that, I’ve actually moved into my next point; punctuation can drastically change the tone of your phrases. The simplest way to demonstrate this is to stick an exclamation point on the end of any sentence! It can add excitement, yes, but only in appropriate instances, in most cases it makes your phrase seem a little ridiculous, but that’s okay. You can always use that to your advantage.

That’s really why punctuation is important, because it chances how someone perceives your piece, visual, conceptual, and auditory understanding are all affected. This is true of any poetic element, and why you should never completely ignore an element if you want to be the most effective poet you can be. True mastery of poetic elements means that you understand how each changes the way your poem is perceived, and using that to further the meaning of your piece.

It’s hard work, and heavy analysis at times, but if you can get the hang of it, it’s the kind of thing that makes Language nerds like me orgasm.

So don’t feel like you have to use punctuation, but don’t ever say it isn’t important.